There’s an extended image that changed everything for me when I was sixteen. I beheld it on a screen at the Belcourt Theater in Nashville.

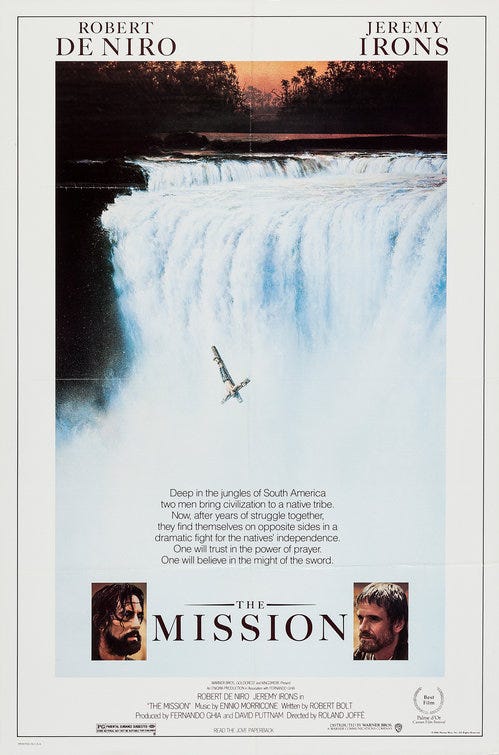

A man tied to a cross is carried down to a river, placed within it with no apparent regard for whether he’ll remain on top or flip over, and then left to stream down to certain death by way of a raging waterfall. In under two minutes, Christianity was placed before me as a problem, a terror, and a thing of beauty. It was the trailer for The Mission. And as a distracted, full, and nerve-wracked young man, I experienced it as a kind of calling.

Weeks later when the film was released, I couldn’t find a single peer who wanted to take it in with me, so I had to go by myself. And here they were: Jesuits. They lived and worked and loved life among the indigenous Guarani of South America in the eighteenth century. Jeremy Irons’s oboe-playing Father Gabriel brought his good news with music, vulnerability, and, once he’d learned their language, words. Robert De Niro’s mercenary slaver Mendoza repented of his lived monstrousness, joined the Society of Jesus and read 1 Corinthians 13 aloud. They were in it for life, bodily invested in a community of mutual enrichment that helpfully rebuked my understanding of missions as an exchange that separated those who do the ministering from those allegedly being ministered to. Very movingly playing for keeps, these Jesuits remained with the Guarani as they were being gunned down by Portuguese soldiers whether it meant dying while celebrating Eucharist or dying returning their fire with fire of their own. The whole thing blew my mind. I stumbled out of the theater into a heavy downpour and wept in my car as I tried to process it all.

I’d never get over it. I felt somehow inspired and chastened all at once. I wanted in. Here was a communal culture with a centuries-old witness of long-suffering love, and little did I know that the most elderly Jesuit in the film, a diminutive, silver-haired man with a penetrating stare and who’d uttered hardly a word, was played by a real live Jesuit who was also an on-set adviser to director, cast, and crew, perhaps the most well-known Jesuit of his time: Daniel Berrigan. I’d be quite a ways into my twenties before I read his words or heard tell of his own beleaguered witness outside the world of cinema, but like The Mission, he would remain a guiding standard in my thinking concerning the Christianity that is the real deal. Real-deal life. Real-deal righteousness.

When Berrigan died in 2016 at the age of ninety-five, his appearance on the front page of the New York Times for the first time in decades served as one more reminder of how profoundly his life defies categorization and, relatedly, how tragically a culture of for-profit news cycles so haplessly ignores a witness as rare and joyful and direct as his. Where do you put the poet-priest who passed his years as a hospice volunteer, a college professor, a fugitive from the law, an incarcerated medical assistant, and a prophetic voice against American war-making? Shall we decree him religious or political? The content cookers of our military-industrial-entertainment-incarceration complex tracking trends and selling advertising can hardly afford to register his presence at all. He doesn’t fit anyones business model. Do we have the capacity and the wit to register and receive his witness?

I sure hope so. I am one who has Daniel Berrigan on my mind most days. An awful lot of what I have to say about most anything is me paraphrasing what I imagine he would say. Sarah and I named one of our kids after him.

But I bring him up now, because I was recently honored by a request to provide a reissue of an old book of his (one I’ve quoted at length in my own work) with an endorsement. I did not see this coming and I could not be more pleased. Here’s comes the blurb.

Daniel Berrigan showed us how to live, how to see ourselves and others and our sweet old world realistically and therefore prophetically and poetically. As his witness demonstrates, this sometimes means seeing the world illegally. Law, after all, is liturgy writ large, and some liturgies we only abide at great cost to our souls. In Jeremiah: The World and The Wound of God, we’re invited to consider the creative task Jeremiah took up within his world and ask what it means to take it up in our own. We could hardly ask for a better guide in this essential sanity-restoring work.

I’m really pleased with this way of putting it. I hope it’ll boost his signal. Here’s a picture of the book.

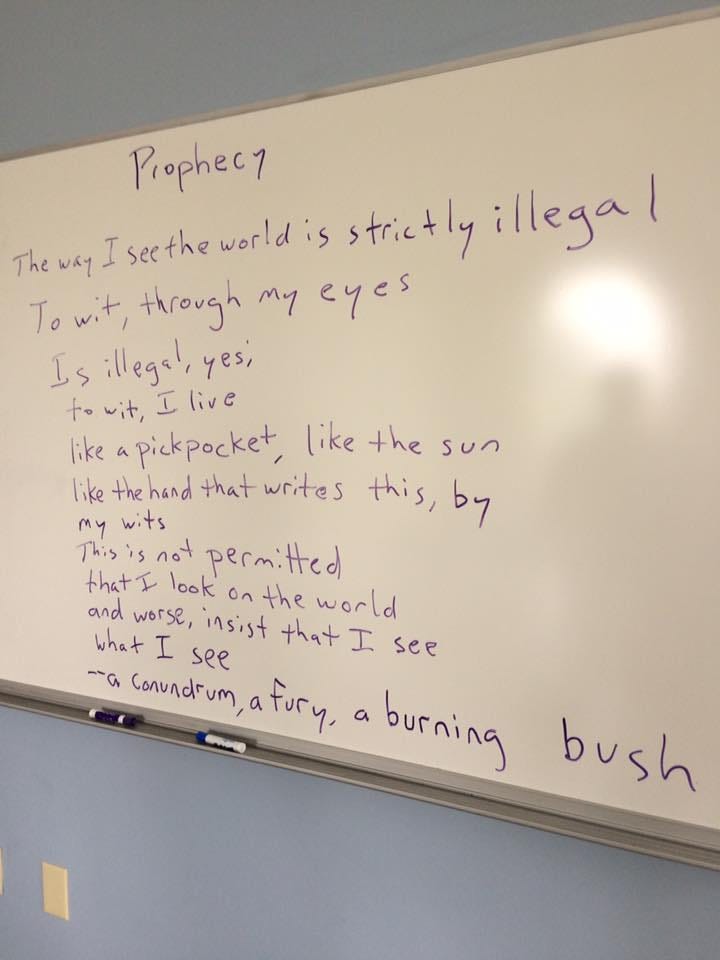

My blurb draws on one of Daniel’s poems. I don’t quite have it memorized, but I write it on the board for students every so often for thinking through the prophetic tasks before us. It’s called “Prophesy.”

The way I see the world is strictly illegal

To wit, through my eyes

Is illegal, yes;

to wit, I live

like a pickpocket, like the sun

like the hand that writes this, by

my wits

This is not permitted

that I look on the world

and worse, insist that I see

what I see

—a conundrum, a fury, a burning bush.

Isn’t that something? Saying what we see. Insisting on saying what we see even when it isn’t permitted. Even when seeing and saying are criminalized. Apply that to your context.

Can I get a witness?

That question is the title of a collection which included my longest piece on Berrigan. Can I Get a Witness?: Thirteen Peacemakers, Community-Builders, and Agitators for Faith and Justice can be found here. And I discuss it at length on our Lived Theology podcast here.

Apart from Robert Gay and Anna Caudill, I don’t know that I’ve ever persuaded anyone to read or research Daniel Berrigan at length, but I love trying to. Please look him up. He goes before us.

I’m almost done, but I have a small housekeeping matter here at Dark Matter. Please consider the image below.

The image is something of a false witness. Yes, you are now able to help fund me and mine (or more specifically…this operation) by becoming a paying subscriber or simply dropping a one-time sum in my coffer, BUT…I have no intention of posting content that’s only for those who pay.

Color me grateful to everyone who wishes to extend me the kindness of supporting my work in this way, but don’t go thinking you have to to behold the bulk of what I’m setting down on this site.

Anybody else moved by The Mission or the poem or Berrigan’s witness? Any questions? Comments?

John, my husband, knew a friend of Daniel and David Berrigan while John was a philosophy professor at Christian Brothers College in Memphis in the way back past. Jerry Vanderhaar was also a professor, a former Catholic priest and a Board member PAX Christi. Thank you for sharing your wisdom, as always. A call to action!

I love The Mission and have watched it many times! Thank you for this piece that highlights not only Daniel Berrigan's life but also the need for truth-tellers who insist they see, yes, what they see in this chaotic cultural moment of ours where sadly, there's plenty of gas-lighting and false teaching to go around.